IDENTX PVT LTD © 2025

All rights reserved.

In the early days of Android (pre-Android 10), it was very simple for developers to get the most reliable, persistent, and unique identifier. The IMEI (International Mobile Equipment Identity) number.

With IMEI restricted, the Android ID became the next candidate for identifying devices. (also known as Settings.Secure.ANDROID_ID or SSAID).

As the Android ID lost its persistence, developers working in high-integrity domains like fraud prevention, finance, and DRM turned to less-documented identifiers for stability and uniqueness.

1. GSF (Google Services Framework) ID

2. MediaDrm ID

The MediaDrm API was originally built for secure digital rights management, not device identity. Yet, it quickly became one of the most persistent identifiers in use.

The fundamental problem with MediaDrm ID is not only its privacy implications but also its unreliability as a true unique identifier. Research shows that a measurable percentage of MediaDrm IDs collide across devices, especially within models from the same manufacturer. Approximately 2.5% of IDs are shared, meaning two users could unknowingly possess the same identifier.

For security systems, this is a serious flaw. A legitimate user might purchase a new phone, attempt to log into a banking or gaming app, and be automatically flagged or banned because another device with the same MediaDrm ID had been blacklisted.

This dual failure of privacy exposure and technical unreliability makes MediaDrm an identifier that satisfies neither developers nor users.

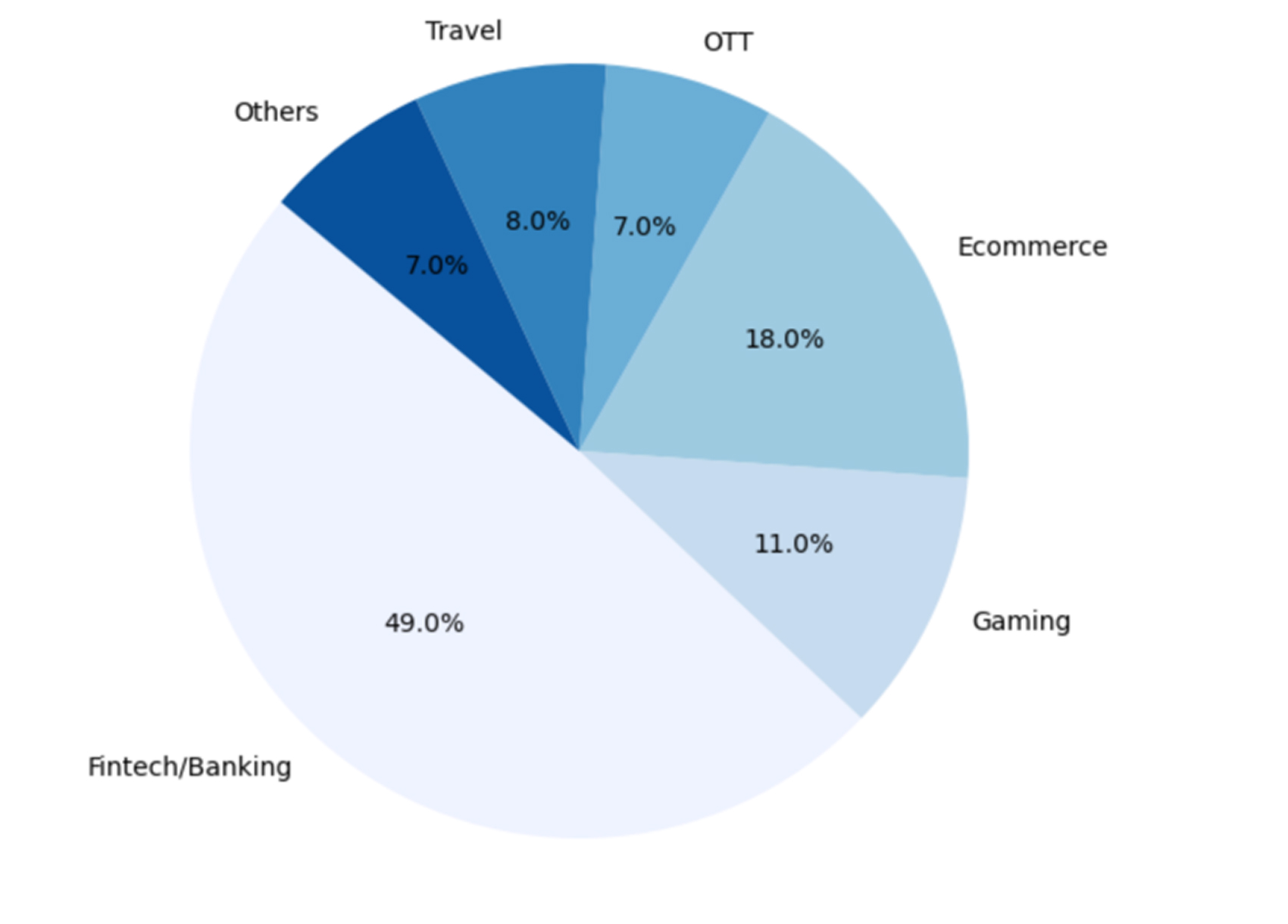

To understand how these identifiers are still used in practice, we analysed over 100 Android applications across multiple domains in India, including fintech, gaming, e-commerce, travel, and OTT.

Nearly 49% of the apps belonged to the fintech and banking segment, followed by e-commerce (18%) and gaming (11%), as shown in Figure 1.

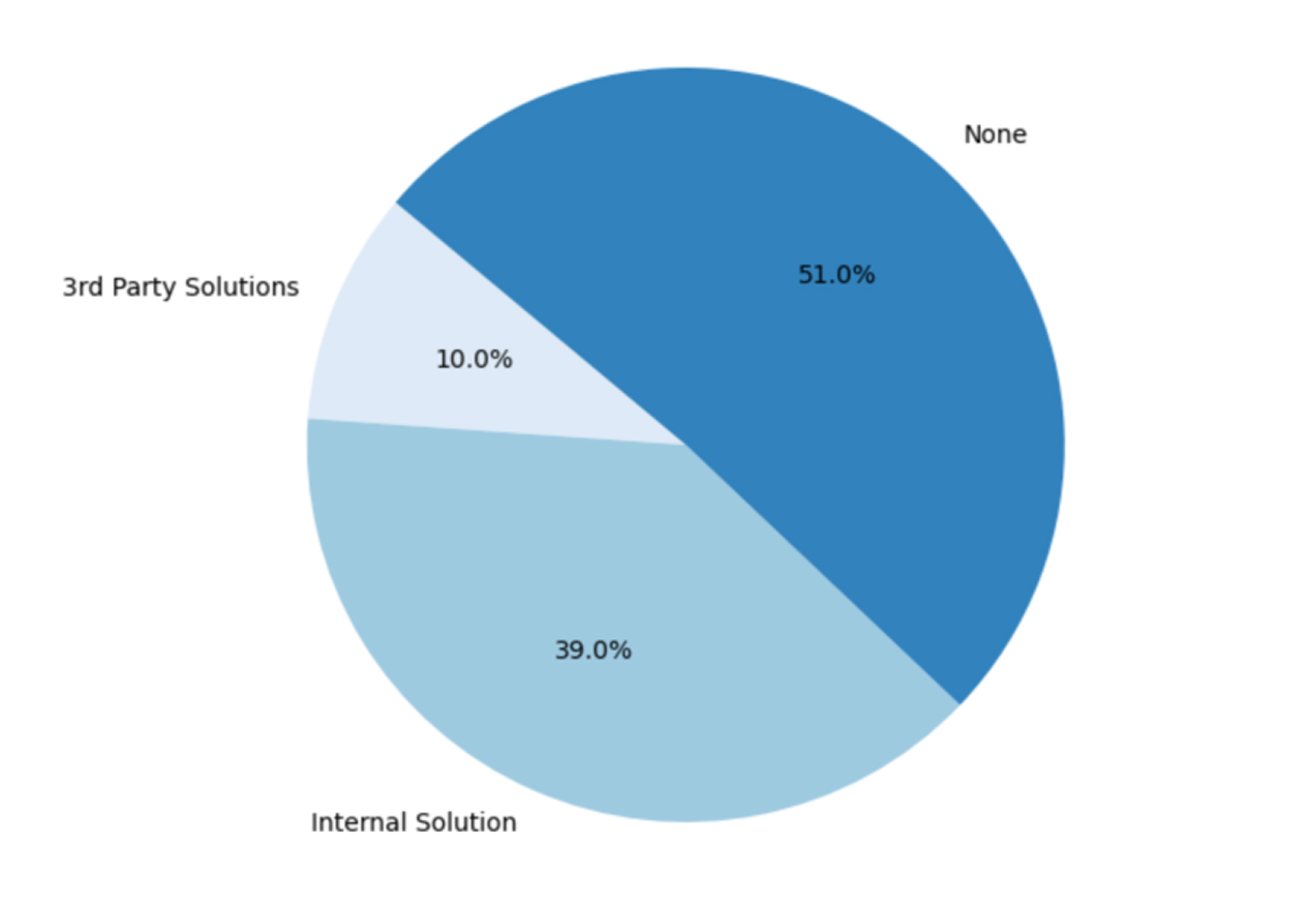

Across these applications, more than half (51%) had no structured device identity framework, while 39% relied on internal implementations and 10% integrated third-party solutions for device identification (Figure 2).

This analysis highlights a key insight: even in regulated or security-sensitive industries, many production Android apps continue to rely on basic identifiers like Android ID, GSF ID, or MediaDrm ID for risk, trust, or analytics workflows. Despite privacy restrictions and spoofing vulnerabilities, these identifiers remain deeply embedded in SDKs and back-end systems.

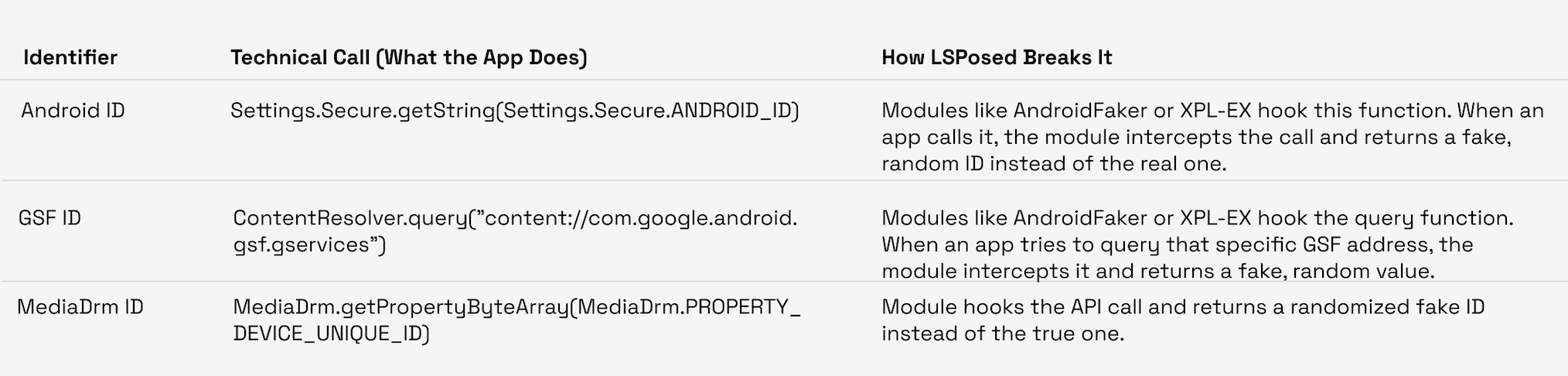

This is where the user’s control comes back. LSPosed is a framework (a successor to Xposed) that allows modules to “hook” into the Android system and apps. These modules are small apps that change the behavior of other apps in memory without touching their original code.

Android’s approach to device identity has evolved from static hardware identifiers to scoped and ephemeral values that favor user privacy. Each new phase has reduced the potential for persistent tracking but increased complexity for legitimate use cases that rely on stable device recognition.

For developers and security teams, the outcome is clear: traditional identifiers like IMEI, Android ID, GSF, and MediaDrm can no longer be trusted as consistent signals of device identity.